Episode 3 Interview with Ken Allen!

PLAY NOW

PLAY NOW

iTunes Feed

iTunes Feed

MP3 RSS Feed

MP3 RSS Feed

Information about Ken and what is covered in this podcast.

- About Me

- My Introduction To Sierra

- The Sierra games I worked on that were my favorites

- Some random memories I have while working at Sierra.

- Events that lead to my departure, and Life after Sierra

- A little known fact about the music for SQ5

- Questions from my Facebook friends

- Conclusion

About Me:

I am one of the producers on one of the world’s leading MMOs called Rift and I’ve been with Trion for about 4 years. I’ve been in the game industry for over two decades and have worked for most of the major companies in our industry, including Atari, where I was the producer for a few installments of the RollerCoaster Tycoon franchise, Interplay, Midway and for Westwood, the company that invented the RTS genre with Dune and Command and Conquer. While at Westwood, I was also a producer on Nox and it was at the time EA had purchased that development studio from Virgin Interactive. So I’ve been around.

Introduction to Sierra:

I went to college to become a music teacher, and after graduation I landed a teaching-job at a private school where I would also be required to teach math. I quickly discovered I hated teaching math and there was not enough call for a full time music teacher. So after 1 semester, I bailed.

I took a job at the post office, sorting mail, while I figured out a plan B for my career. Meanwhile, I wrote lots of music for local theater and churches and taught myself to write computer games in BASIC and had begun to learn a little assembly language. The MIDI era had just dawned and I built a home MIDI studio which would allow me to produce music as well compose it.

In 1989 a classified ad in the Fresno Bee was brought my attention that basically read “Musician needed for video games.” It was for Sierra On-Line. But I thought there was no way this was a real full time job because it seemed too good to be true.

I was familiar with Sierra because my best friend from college had a PC JR and I watched as he played Kings Quest 1. But I never played any of their games because I had invested all my computing money in Atari gear.

So I thought what the heck. I found a service to help me write my very first resume, and I recorded a tape of music I had written. I really wanted to impress the people at Sierra, so I wrote a brand new piece of music to show that I also could work very quickly with a high degree of quality. If I ever find that recording I’ll put it up on youtube.

A little more than a week later I got a call from Tammy in Sierra’s HR department, inviting me for an interview. I made the 40 mile drive from Fresno up to Oakhurst to the Sierra HQ, where I met Stuart Goldstein a systems programmer who was devoted to writing code for the music technology and tools we would use to put music in Sierra’s games, Mark Seibert another music guy who would later become head of the music department, Rick Cavin head of operations and Ken Williams, founder of Sierra. In passing I also met Guruka Singh who was a kind of game producer at a time when the game development industry was just formalizing that role, and Chris Iden who was one of the lead programmers who would later become Director of Game Development.

While I waited to be interviewed, Tammy gave me written timed IQ test. I bombed it because I let myself get stuck on one question instead of answering all the ones where I knew the answers, and then going back to the tough ones. Later Tammy told me not to worry about the test; they only used it to see if a candidate was super smart, in which case they would really want to hire that person.

The interviews went well, but I knew I had some competition and was a little nervous because it became pretty clear this was not a part-time temporary job as I first suspected. Sierra had just gone public and they were expanding. The next new thing in home computers in 1989 was sound and music and they were hiring musicians who could help them take the lead in that category.

When I met with Rick, the head of operations, we started talking about salary. I never had to negotiate salary before so I blundered my way through it. Here was my pitch. I told Rick the amount I was currently making and that I would be willing to take a significant cut in pay to prove myself, and that after a probationary period of 90 days, if Sierra liked me they would boost my wage to the pay-scale for that position. He agreed.

About 10 days later, I got a phone call from Tammy with a job offer, to which I replied how soon can I start, and on April 7, 1989 I began my career in game development making music and sound effects. I was able to tell all my friends and family I made a living sitting around making funny noises. It was all great fun. Two of my favorite loves, music and games, had come together and helped me launch a new career.

But the unfortunate thing was that Rick neglected to keep a record of this agreement and pay became an ongoing issue. It was the eventual reason I left. I think it was one of those things that just got lost in the shuffle. Things and Sierra were evolving quickly and a verbal agreement like this was bound to get overlooked

Favorite Games:

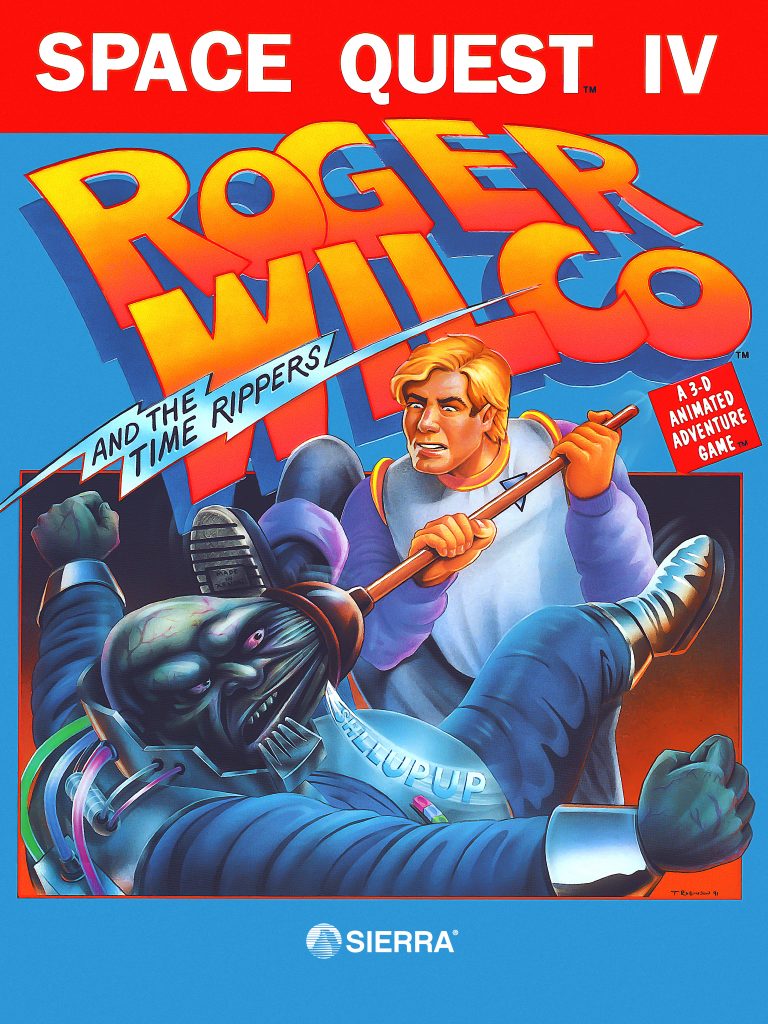

Of course working on the Space Quest series was my favorite. I don’t think any other game has been able to match the quality humor in those gems. And I had composed my brains out for the two guys.

Working on a few Kings Quest games was also fun because it was Sierra’s flagship title.

I think I did about a dozen games in all for Sierra. Plus I also did the theme that appears as the Sierra logo appears at the beginning of each game.

One of my other skills was creating sound banks for the various sound cards hitting the consumer market. I had a knack for creating high quality instruments and sound effects using the synth technology of the day. Truth is, I’d built a synthesizer from a kit in 1978. I was a smaller version of the Moog synthesizer depicted on the cover of Switched on Bach. The way you created instrument sounds in those days was to link syth modules together with patch chords and twiddle some knobs until you got the sound you wanted. The software we used at Sierra to create custom sounds was pretty much the same thing.

But when General MIDI hit the music industry, the sound cards quickly adopted it. And it was my job to create a General MIDI sound bank for all the popular non-General MIDI sound cards supported by Sierra’s games and from then on, Sierra pretty much just used General MIDI in all their games. Sound effects would be done through sampling.

Memories:

Rolling Stone magazine came up to Oakhurst to interview several employees for a feature they were doing to profile Sierra’s 10th anniversary. But Kirk Green, head of PR, told me a few weeks later the piece had been pulled because Saddam Husein had just invaded Kuwait and that Rolling Stone had to make room for war related stories.

—

I proposed the name “Slater” for the dinosaur character in the game Oilswell. Later Sierra did an educational game called Slater and Charlie Go Camping.

—

I remember the moment the idea for the Sierra Network was born. I was working late, and Al Lowe strolled in to the office with a Commodore 64 under his arm. He hooked it up to a monitor and used a dial up modem to log into a service called Club Caribe. I encourage listeners to this podcast to lookup Club Caribe and Lucasfilm’s Habitat in Wikipedia. It will be an enlightening to read about how the whole online game world came to be.

Anyway, I heard Ken Williams and Al Lowe laughing so I wandered over to see what was going on. Al Lowe was moving his avatar through an island-looking area on the computer monitor. It was basically a graphical chat room. There were about a dozen other people in the room and Al Lowe was telling jokes like a stand-up comedian. I could hear Ken and Al talking about which of Sierra’s games could be repurposed to be played in an on-line room like this. The Hoyle series was a no brainer, and Jones In the Fast Lane could be turned into a turned based board game.

This was pre-AOL days and the only other real players in online games were text-based MUDs hosted by local BBSes, a few text-based offerings from services like Compuserve and Prodigy, and a game portal company called PlayNet that offered familiar board games and a D&D MUD. Ken Williams was a true visionary. He and Roberta were a key players in launching the video game industry and he saw the potential of online gaming almost before anyone else. He was a good 10 years ahead of his time, maybe more.

I did many of the sound effects used in the UI for the Sierra Network, but developing TSN was expensive and I don’t think it ever became profitable. Not long after I left Sierra, they sold the division to AT&T where it was renamed Imagination Network.

—

I remember the first time I experienced falling snow. I grew up in Sacramento, went to college in Southern California and was currently living in Fresno. I’d never seen snow falling from the sky until one day I walking through the Sierra parking lot in the dead of winter.

—

We had a lot of “Firsts” at Sierra. I believe we were the first to develop games for the FM Townes computer that was being introduced in the US.And I’m fairly sure we were the first to use redbook audio in a CD-ROM game; it was Mixed Up Mother Goose. Previously we’d updated the game to VGA resolution and I did fresh new arrangements of all the songs. For the CD-ROM version, we recorded studio-quality versions of my arrangements using the equipment from my MIDI studio, and then we recorded the vocals using a local church’s kids choir Mark Seibert’s wife directed.

—

I remember rumors that circulated through the company that someone from Sierra had contacted Duracell to gain permission to use the Energizer Bunny in SQ4, to which Duracell said “Sure use our bunny.” Energizer owned the Energizer Bunny, not Duracell. And Sierra got sued. But, I think the story is apocryphal because I doubt Duracell would actually say “sure use our bunny” when they didn’t have a bunny.

—

Early in my tenure at Sierra, a movement to unionize the workforce developed. As I recall, us non-management lackeys were going to be represented by the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers International Union. Mainly because this was a union for a high tech sector. Sierra worked very hard to put down the union uprising. They didn’t break any laws. And eventually, the unionization movement petered out. One of the union organizers was eventually fired because he violated company policy against using company equipment for personal use. Sierra Management found astronomy software on the office PC of that person. We all saw it as a shot across the bow.

—

You know that scene in SQ3 where game developers are confined to their cubicles and the manager walks above them on a catwalk whip in hand, issuing an occasional crack of the whip? I saw a couple weekends at Sierra where a similar version of the scene unfolded for real. I don’t recall which game they were working on, but the head of operations walked around the cubicles where the dev team was toiling; they were under a very tight deadline.What else… I walked past the board room and saw Louis Castle and Brett Sperry (founders of Westwood) were demoing Legend of Kyrandia in hopes of landing a publishing deal. Sierra passed on it but Westwood completed the game and self published it. I remember the ads “If you like Kings Quest, you’ll love Kyrandia.” Which I think also appeared on the box of the first installment of the series. I think there were threats of lawsuits over the use of Sierra trademark. But, yeah, I was in the room, albeit briefly as the game was pitched.

Leaving Sierra Afterward

After being told again there was no money in the budget for a salary adjustment, I started looking at my options. First I considered staying with Sierra and trying to do what Scott and Mark were doing, leading a project of my own design. In those days, lead designers were in charge of developing games, but they also had another skill, like art or programming. I enrolled at the local community college and signed up for a few semesters of C programming. After I completed my course work, I went to Chris Iden, head of game development, and asked to be trained as an entry level programmer because I wanted to move over to the engineering division. The head of the music department objected because I was his most valuable asset. I’d trapped myself into being indispensable and there was a lot of work on the horizon for the music department.

So I started looking outside Sierra.

Accolade had release a Sierra-type adventure game and were producing a sequel. I called other game companies and found that I’d made a name for myself and could probably make a good living producing game music as a contractor. So after I got a verbal commitment from a few game companies, I met with Mark Seibert and tendered my resignation, 30 days notice so I could finish The Island of Doctor Brain. I think he thought I was bluffing because there had been a string of people threatening to quit over pay who ended up staying because Sierra met their demands. If you wanted a raise, that was kinda how it was done. I’m pretty sure he thought I was pulling the same stunt, but I believe he decided to call my bluff. Not 100% sure, but that’s my thinking.

He reported my resignation to his boss, Bill Davis, Sierra’s Creative director, one of the coolest guys I’ve ever known, and Bill worked really hard to convince me to stay. He agreed I was very valuable and that I was indeed doing twice the workload of anyone else in the department. I told him I looked outside the company and discovered I could increase my income as an independent contractor by more than 50%.

So Bill asked what it would take to keep me, and I said if he could match what I could make on the outside plus throw in a few thousand stock options, I’d stay. Bill declined to match my suggestion and I have a sneaking suspicion it’s because it would put my pay above my boss’s. I was out that day.

Ken Williams made one last pitch. He told me I should have come to him if I felt I was being treated unfairly, but I told him this was something I didn’t know was an option, that I thought I needed to work things out in the chain of command that was in place, and that when my bosses told there was no room in the budget, I believed them and made some decisions based on what they told me. I told him I was not the kind of person who would threaten to quit in order to get a pay raise like some others on the staff. After Sierra, I did game music and sound effects for several more years. I did a few games for Accolade, Disney Interactive, a small studio in the bay area called Futurescape, Tachyon (formed by ex-Sierra people), and Interplay (I think my sound effects for the Nintendo version of Starfleet Command got an award from Nintendo Magazine) plus a couple of song packs for the Miracle Keyboard. I had approached Access, Westwood, LucasArts, Legend, and a few more that don’t immediately come to mind. I was well on my way.A few other ex-Sierra employees had gotten together under Ed Heinbockle (the form Sierra CFO who help take them public) to start up a company called Tsunami Media. They invited me to do all the music and sound for their games and eventually hired me so I could exclusively do music just for them. I accepted the job offer from Tsunami on the condition I would be allowed to also become a game designer and they agreed.In addition to music and sound effects, I also did level design on Protostar(a game originally intended to be sequel to Star Control), and was the lead designer / producer on Ringworld 2. I did a little bit of everything at Tsunami; music, sound design, directing the voice talent, designing, writing, writing user guides, a little IT work. They nicknamed me the Tsunami Renaissance Man. My hope was to help build Tsunami to repeat the success of Sierra. But there was an ongoing lawsuit between Ken Williams and Ed that was a drag on the company. When it became clear that Tsunami’s days were numbered, I took a job with Interplay as an external producer. I later transitioned to internal producer to head up development of a Star Trek adventure game called Secret of Vulcan Fury, which never was released. But the reason for that is a whole other story.

If you look at my Moby Games profile, you’ll see at list of about 50 games, and there are about 10 more that should go on that list, because many games I worked on don’t list credits.

SQ5

Something only about 5 people in the universe know is that I actually did the complete score and set of sound effects for SQ5 for Mark Crowe at Dynamix. He was no longer at the home office in Oakhurst and the distance gave Dynamix a little more freedom to hire contractors of their choosing.

I finished all the music and sound in a couple months, and I got paid the full amount, but after I completed the work, I was a little careless and let it slip to a Sierra employee (I can’t remember who) that I had done the SQ5 music.Ken and Roberta were vacationing in Barcelona during the the Olympics, and from what I heard, when he returned he was informed of my involvement and ordered my music be pulled and replace by music composed by Sierra employee composer Chris Stevens.

I can’t blame Ken for this decision. I mean, I wouldn’t an ex-employee somehow weaseling in and taking a staring role in the development of a flagship product. But at least I got paid. I’m pretty sure most, if not all, my sound effects survived, but the score I wrote for the game is probably lost to the world. Oh and if someone does have those song files, please let me know.

Questions from Facebook and Twitter

What were my musical influences? from Adam Vujic in Australia via Facebook

My favorite composer was Jerry Goldsmith, who composed the music for Planet of the Apes, 4 of the Star Trek movies, Hoosiers, Rudy, Patton and a ton more. In fact, the Patton film score made me want to be a composer. I was awestruck by the film’s music and it was the first movie soundtrack album I ever purchased. After I left Sierra, I signed up for some film scoring classes at UCLA, and one of the classes offered was an all day session taught by my hero, Jerry Goldsmith where he talked about the decisions and musical techniques he brought to bear while scoring Rudy. He signed my copy of the soundtrack album (which I have framed in my home office) and generously posed for a photo of the two of us.

Did I find it difficult given that there were several sound cards around of varying quality. Did I have to adjust the instrumentation for each to ensure the score was faithfully reproduced? also from Adam Vujic

There were really only two types of sound cards when I started at Sierra, those that used FM synthesis (the kind used in the Yamaha DX7) and those that used Addative synthesis from Roland, and the FM synthesis had two categories, 2-operator and 4-operator. Plus we supported the Tandy 3 voice chipset which just simple sine waves, no synthesis, and the PC speaker. So, yeah it was a challenge. We had to adapt each song to play on each of the 5 different playback devices. But when General MIDI became the standard for all sound cards, it became much easier.

Alistar Gillett of Tulsa Oklahoma asked the following through Facebook:

1. Firstly, is it cool reconnecting with all the old Sierra folks? I imagine some of them you probably haven’t come across in 20 years! (Also on Facebook Sierra alum, Marty McKenna, asked “What was is like working with me?”)

It was a totally blast working with all the people at the Oakhurst office! If I start listing names, this podcast will go on for hours and I sure I’d still leave someone out, so I won’t even start. Working at Sierra was something real special. In spite of some of the unflattering stories floating around, we all felt very lucky to be working there. Ken Williams had a keen awareness of where computer games were going and I saw the beginnings of Sierra’s transition away from just doing adventure games and embracing new genres, like arcade games, strategy games, educational games and casual games I’ve had infrequent contact with most of the ex-Sierra crowd. But reconnecting is always a joy.

2. Josh Mandel recently suggested you help with music for the Two Guys’ new project, SpaceVenture. Obviously you work for Trion now, but- thoughts?

I love Josh. We’re part of our own little mutual admiration society. I did music for his game that Legend published, but did so under a pen name so I wouldn’t get fired for conflict of interest. The announcement from the Andromeda guys has inspired all of us connected with the original franchise to imagine all sorts of possibilities. Those are my thoughts. By the way, Josh, I think I owe you about 10 bucks for all the little candies I consumed that you had on your desk for visitors. The check is in the mail.

3. What is your favourite piece of music you ever composed while at Sierra?

Obviously the opening sequence for SQ4. There’s actually a funny story behind that. When SQ4 was kicking off, I lobbied hard to get tapped as the game’s composer, but Mark Seibert had already assigned me to a couple other projects. One day, he took a couple weeks vacation time and while he away, he delegated minding the music department to me.

During this time the two guys from Andromeda came to me is a bit of a panic because Sierra, now a public company, had regular board meetings where progress on the various games in development would be reviewed; and SQ4 was on the scheduled meeting that was only 5 days away.

So Mark Crowe and Scott Murphy came to me and said, we need music for the opening sequence and we need it like Monday (it was Friday or course). So I went to Bill Davis, told him the predicament and suggested we video tape the opening and I’d crank out the music over the weekend. He agreed and gave me 20 bucks to go buy some video tape for that purpose.

As we recorded the video, Mark Crowe told me exactly what he wanted in terms of musical style, and sound effects that were needed for each scene, he was very specific even giving reference to sounds used in sci-fi movies (like the sound of the device used by Dekker in Blade Runner where he was studying the photos found in the living quarters of a replicant he’d just killed).

Scott had just had one point of direction, “Knock our socks off, Ken!” So that’s what I did. I got almost no sleep that weekend and when Monday came around, I uploaded the sound files to the company’s file server and met with the two guys to go over my work. They plugged in the tunes to the game and launched it. As the music played, I remember watching their reaction, sitting back with their arms crossed watching the game opening unfold with the big orchestra underscore. Mark Crowe, who normally smiles with a kind of side smirk, actually revealed his teeth as the music continued to play. Mark wanted only one change, the cantina had a futuristic honkytonk tune that he didn’t care for, so the next day I brought in something more akin to the Star Wars cantina music. I heard through the grapevine that during the board meeting, Roberta, who was also present, asked her husband why the music for her games did sound as good as the music for Space Quest – but I don’t know for sure if that’s true.

Mark Seibert came back from vacation a bit surprised by what had developed in his absence, but I was reassigned to work on SQ4. I think due to the insistence from the Andromeda guys. I went on to score many of the high profile games at Sierra after that.

4. What was your favourite project while working at Sierra? (Don’t say some Adlib conversion!)

SQ4 was by far my favorite, but also had a ton of fun composing for the remake of Oilswell. Between each level of the game was a little vignette featuring the game’s dinosaur mascot, Slater where something spectacularly wrong would happen to him. It was like writing music for a cartoon. This was the kind of influence Bill Davis brought to Sierra. I think Bill actually won a significant award for the cartoon opening of the movie City Slickers while he worked at Kurtz and Friends in Hollywood. GREAT FUN!

5. What is your favourite music style, and what inspired you then (1989-1991) and now?

By far I like composing for orchestra. Go to my YouTube channel (youtube.com/mrkenallen) and you see a trailer for the Star Trek game I was designing and producing for Interplay. That’s my music being played by a 40 piece orchestra of Hollywood musicians and I’m the conductor. Standing in front of 40 professional musicians playing my music was VERY gratifying. But I taught myself to write in any style and did so for many of the games I worked on, including big band, rockabilly, technorock, classic rock, bluegrass, cartoon music, practically everything.

One of my Facebook friends asked in jest if I had to learn to speak Andromedan when working with Mark and Scott on Space Quest? And if my Andromedan, he meant “humor” the answer is yes, I had to learn the language of their humor.Piers Sutton also on Facebook asked this question:

Richard Garriot and Chuck Norris walk into a bar; what type of music plays and why?

This is exactly the kind of question I would expect from a fan of Space Quest. And in that spirit I will say Yakkety Sax (the theme from the Benny Hill show). Why? Because it’s funny.Many of my colleagues ask, when they find out I did music for some pretty famous games, why I gave it up.Pretty simple really, money. My earning potential as a game composer was lower back then than for other game development categories, although that’s changing now. Originally, I wanted to do programming and game design and I wish I’d actually made that choice in the early part of my career. Writing music is a lot like writing computer code. The language is symbolic, there’s conditional branching, and when you write for several musicians, it’s multithreaded. So yeah. I do miss writing music. But I really do love what I do now.

![]() PLAY NOW

PLAY NOW![]() iTunes Feed

iTunes Feed![]() MP3 RSS Feed

MP3 RSS Feed

wow good read!